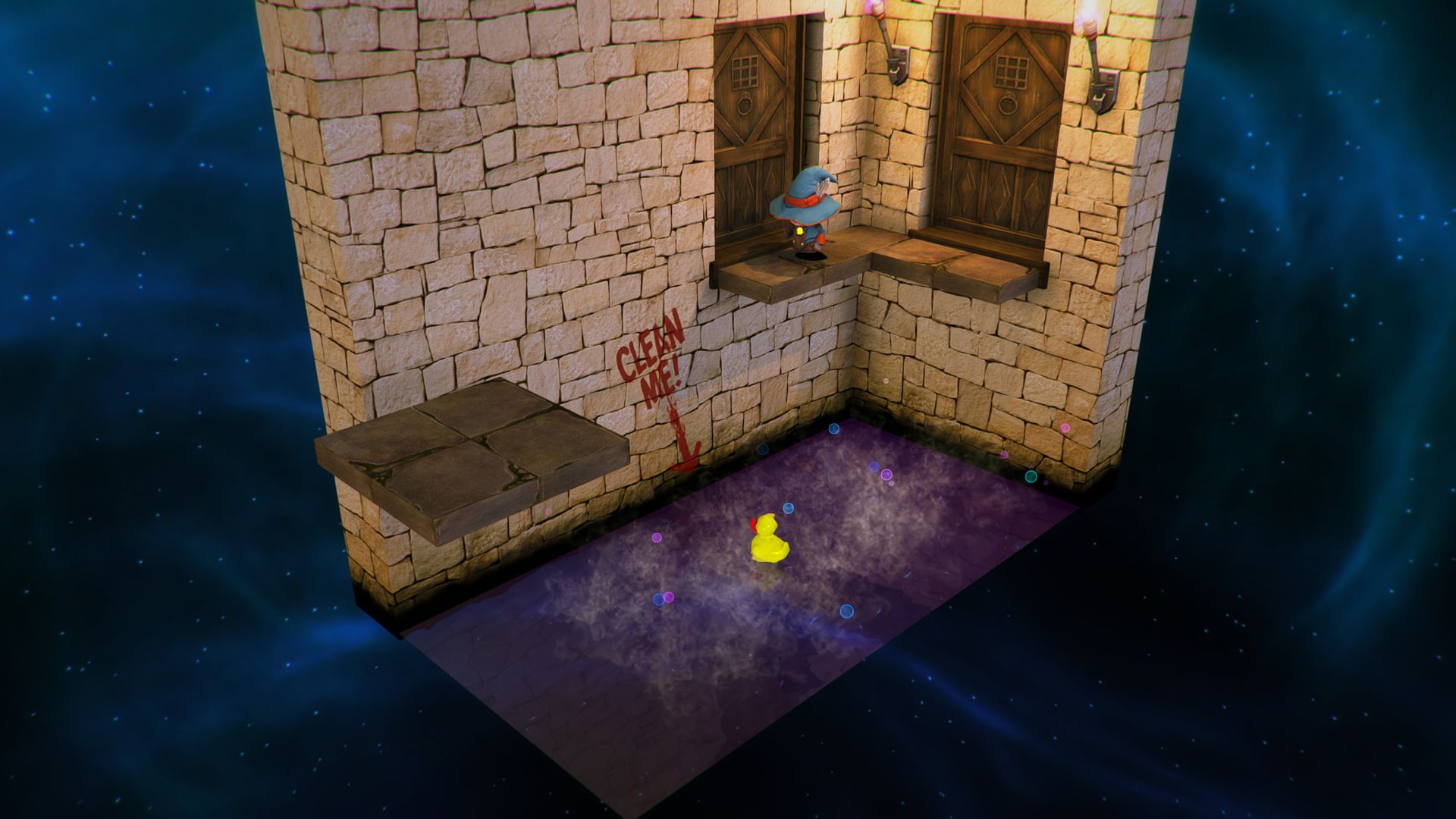

You start in space, floating amongst the stars in an exposed room with only a floor and two walls. The room is dim and lifeless as your character, a funny little boy in a pointy, oversized witch hat, teleports in. He takes stock of his surroundings, then sneezes, igniting some torches by a door.

That’s where your adventure begins in Lumo, a charming throwback puzzler.

The entire game is played from a pulled-out isometric view that prohibits you from seeing anything developer Triple Eh? doesn't want you to see. You can’t rotate the camera around to peek around objects or get a more tactical view of the environment, so you’re going to need to learn how to think within the bounds Lumo presents you. This might mean you enter a room with a few small floating tiles you need to jump on to get to the next door, but some of the tiles are slightly obscured; you’ll need to make do with the perspective you’re given and play carefully if you want to succeed.

When you leave a room, everything disappears and you’re left simply in space for a brief moment. As it returns, you’ll be presented with a new room’s layout, a new puzzle to do or challenge to complete. Every room feels like a new small surprise to uncover, almost like the microgames in a WarioWare title. Sometimes you’ll enter a room and there’s a spinning fire trap you need to avoid; sometimes there’s no present danger at all. These traps get much more complex the deeper in you get, with laser beams, air jets, poison pits and more. It’ll be interesting to see how complex Lumo will get by the end, especially given the relatively limited mechanical toolset you work with when controlling your character.

Controlling the little boy in Lumo feels a bit like playing Captain Toad’s Treasure Tracker: he’s small and walks with a charming, bouncy cadence and isn’t exactly the most nimble guy. Unlike Toad, he can jump, but overall he feels similarly restricted in what he can do, especially taking into account that in Treasure Tracker, moving the camera around to reveal secrets and pathways through each level was a big part of that game’s design. Lumo manages to evoke the same relaxing feeling that Treasure Tracker reveled in while layering on secrets of its own.

Several times throughout the demo, I was able to find a way to clamber onto a shelf and make my way up and over the walls right into space, leading to a new room with a reward. It felt rewarding in the same way it was rewarding in Super Mario Bros. for the NES to jump on the top row of blocks in the underground Level 1–2, walk safely above all the hazards from the rest of the level, and drop into the Warp Zone.

There’s a calming feeling to moving from room to room in Lumo, and none of the traps (at least in the demo) are particularly demanding, so it became easy to fall into a bit of a trance while playing Lumo. It’s not exactly the most exciting game in the world, but if Lumo manages to ramp up the challenge while keeping the design clever, it could be a strong contender as the kind of game you plop down with, lean back and enter a slightly meditative state as you get lost in the maze.

Lumo will be out later this year on PlayStation 4, PlayStation Vita, Xbox One and PC.