House of Caravan is billed as “Gone Home meets The Crimson Room meets P.T.,” which invites some lofty comparisons. Here’s how the game is supposed to go: you play a child who is kidnapped by a strange man on the way home from school and brought to an old manor deep in the woods where the locals dare not tread. With a bit of ingenuity you manage to sneak out of your room to explore the darkened halls of the old manor, trying to find a way back to your mother. As you wander, strange goings on keep you on edge, and you feel a sense of mounting dread that something isn’t quite right. Notes scattered throughout the house reveal the sinister truth behind your abduction, and detail the sordid history of the Caravan family.

Here’s how my playthrough went: I fumbled around in a darkened room for a few minutes, first finding some matches to light the surrounding candles, then a key to open the door. Before I could leave, the game froze me for a few seconds and played a low rumbling noise while shaking the screen. At the time I couldn’t tell whether this was meant to be an earthquake or the movements of some eldritch abomination beneath the manor, but either way I was glad to have the scripted annoyance out of the way early. After all, no developer would be silly enough to repeat the same scare twice – or like forty goddamn times – right?

On the way out my eyes were drawn to a room across the hall, its door slightly ajar. “Ah,” I thought to myself, “here is where the developers want me to go next – the positioning of the door is inviting, and my eye is naturally drawn to the light inside as it contrasts with the darkness around me. Horror design 101.” The door lead me to a bathroom with nothing in it, a dead end which I’m pretty sure was just put in by the developers to fill space in the house’s layout. Having seen the game fail utterly at a fundamental principle of level design in the first three minutes, I lowered my expectations significantly. It was not enough.

In a drawer I found a flashlight, which – despite having all the luminescence of a firefly fart – died on me after approximately three minutes of use. Actually, now that I think of it, the light may have just decided to stop working – I found batteries later, but pressing the F key didn’t seem to do anything even then. Whatever the reason the flashlight stopped working, and I was once again stuck wandering the pitch black halls. I’m not entirely sure why the house was so dark – the halls were full of candles and lamps, roughly half of which were blackened, and of the seventy or so chandeliers I passed on my way through the house, exactly zero were lit. I guess not making any logical sense is one way for a game to feel unnerving.

As I headed for the stairs a window flew up and a gust of wind blew leaves into the hall in a jump scare so inept that I laughed out loud for a solid minute before continuing. Shortly thereafter I was stopped again for yet another earthquake – as it turned out, the event was not scripted at all, but rather set to randomly trigger every seven minutes. So not only did someone think that forcing the player to stand stock still for several seconds was a good idea, but the rest of the team liked it so much that they made it happen all the time forever. House of Caravan was starting to get on my nerves.

Eventually I stumbled into an open room – another useless bathroom, it turned out – and then I found the dining room and kitchen where I discovered a preposterously generic puzzle. In one corner there was a lock box with several letters and numbers on the front, and nearby I found a photograph with a letter and number “hidden” on a sign in the foreground. It took me less than a second to figure out what I had to do, and I could have brute-forced the puzzle in under a minute based on how it was designed, but the game wouldn’t even let me attempt to solve it until I went through the rigmarole of finding another picture elsewhere in the room. Like random earthquakes, aimless busywork was starting to become a motif.

I distracted myself from the tedium for a bit by redecorating the dining room. House of Caravan’s best gameplay feature by far is the ability to pick up any object in the environment and carry it around. Paper objects are rigid like wood, and it’s all too easy to balance them on their edges when you put them down. Things like jars and glasses can of course be broken. In fact, it’s more or less unavoidable since they shatter with even the slightest nudge, at which point they become impassable obstacles. It’s not just small objects like in Gone Home either – the game lets you pick up chairs and other furniture to rearrange as you see fit. You can also make a merry little jump at any time to climb on top of the chair fortresses you build – probably not a wise feature for a game that’s trying to be scary, but endlessly entertaining nonetheless.

Once I had the puzzle solved I went upstairs. Yet another earthquake happened, and after mistakenly wandering into yet another empty, useless bathroom I was confronted by yet another lock box with yet another combination that I had to deduce through yet another round of busywork. My patience was starting to run thin until by chance I happened to look down while holding a book and found myself suddenly floating just below the ceiling. After a bit of experimenting I discovered that any small object would have a similar effect, pushing me up and allowing me to fly as though I were palette jumping in Half Life 2. After fiddling around with an open book for a few seconds I managed to push myself through the ceiling, at which point I rocketed skywards as though I’d just been ragdolled by one of Skyrim’s giants.

And here, finally, the REAL game began – a game I like to call “how badly can I break House of Caravan?” From my vantage point miles above the world, I could see every room in the house – including the ones behind locked doors. I could also move around in midair, allowing me to drop into any room I wanted, including a hidden passage behind a bookcase. After futzing around in a few other rooms with more awful puzzles that I assume were supposed to lead to that passage, I cut out the middleman and hopped over the shelf. The passage took me downstairs to what I can only describe as a torture dungeon, which happened to be adjacent to the garage for some baffling reason – remember, nonsense is unnerving!

In the murder basement I found a generic circuit puzzle which I solved in about two seconds several years before I ever played House of Caravan (for some reason all of the circuits in old houses like this are built with multi-directional wiring attached to rotating panels on a grid), but I needed to connect the breaker to another box to make it work. Over in the garage I was startled by a window breaking because I’d forgotten that the game was supposed to be scary, and I went to examine the workbenches beside the walls. I found a wire in one of the drawers, but for reasons beyond my capacity to care anymore I couldn’t make it connect to any of the ports on the circuit breaker. Then I was frozen by another earthquake. Knowing that the next room could only possibly be a bathroom anyway, I turned off House of Caravan and immediately started to write this review, because I knew if I waited that everything but the glitches would slip my mind.

It may seem like I’m being unfair to this half-baked independent nightmare (to clarify, I don’t mean the good kind of nightmare), but if I hadn’t discovered all of the hilarious physics glitches this review would be a LOT harsher. House of Caravan is a very poor excuse for an adventure game. It’s built on the most derivative, tedious, and uninspired puzzles I’ve ever had the displeasure to click through. The titular house is equally boring and forgettable, but generic as it is the developers somehow managed to fundamentally screw up on several basic level design principles.

You’d think it would be difficult to screw up a game like this, but Rosebud Games has managed to highlight by contrast just how much work the Fullbright Company actually put into Gone Home. Their attempts at scare tactics range from irritating to outright laughable, and their idea of mood lighting seems to be “shroud everything in a blanket of impenetrable darkness” – a little creepy, but mostly annoying in a game about searching for things. The interface is an atrocity – you have to right click to bring up your inventory, then right click again and again to cycle through it one item at a time – and just getting around can be a chore when physics objects decide to become impassible.

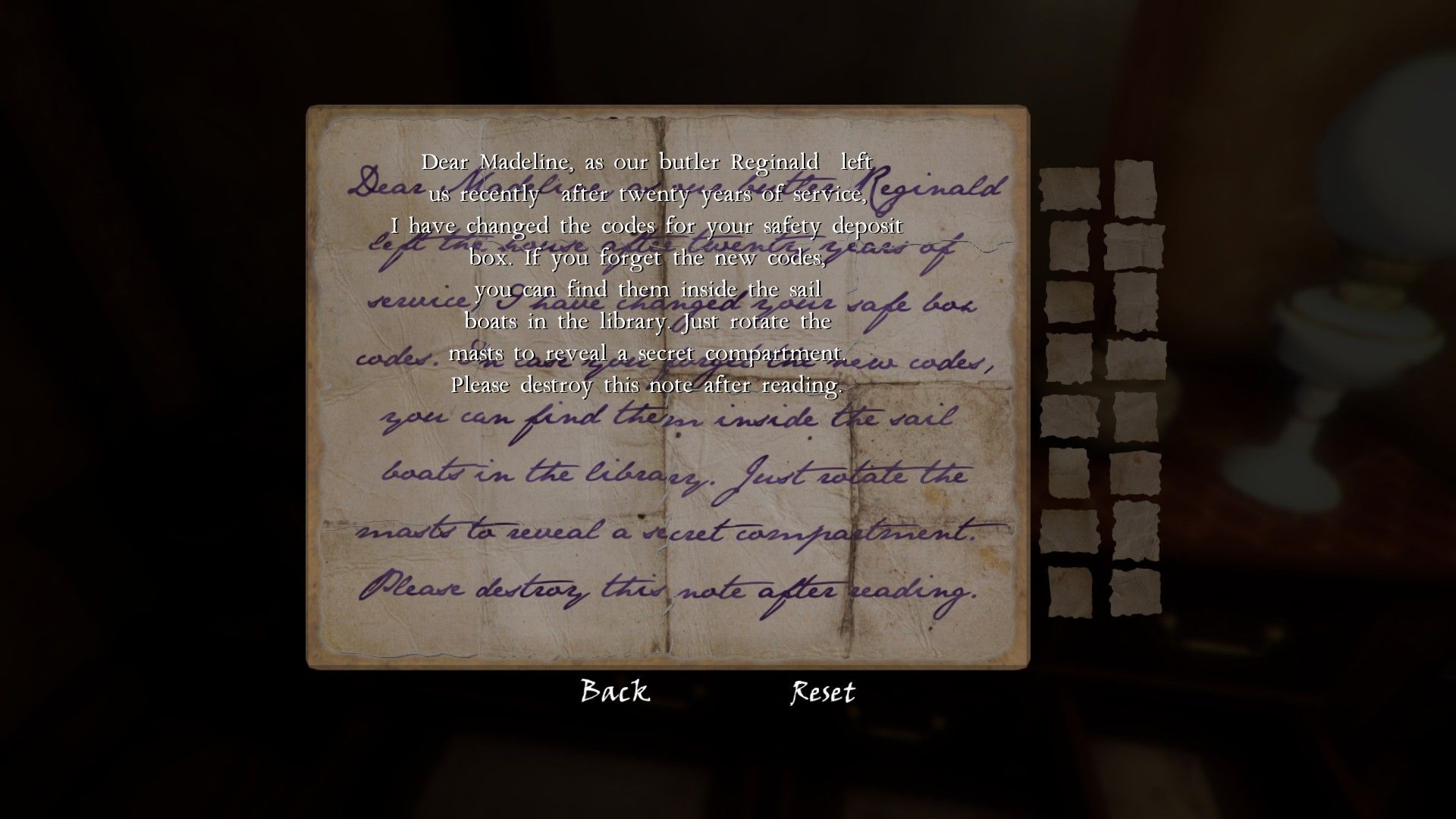

On top of that, the story that the game tries to tell is both clichéd and poorly written. Hidden notes read more like itemized exposition checklists than things that an actual person would write, and the narrator voicing them sounds like he or she (I honestly can’t tell) is about to slip into a coma. What few “twists” cropped up in my playthrough were as predictable as they come, and while the game might have a genuine surprise waiting at its conclusion, it failed to get me invested enough to pursue it. I got to a point where the bugs were the only thing keeping me playing, and once that novelty wore off I quit.

Closing Comments:

House of Caravan’s physics are broken beyond repair, but if anything that turns out to be a welcome distraction from a game whose “key features” include – and I’m paraphrasing here – “you have to turn most of the lights on yourself!” Rosebud’s claims of “top-notch graphics” are a little more appealing, and even accurate if they were going for a house where everything is made of wood, but that’s just about all the game has going for it. This game is a total waste of time and money, and the best I can really say for it is that it doesn’t waste much of either. In fact, in a day or two, you’ll probably have forgotten it entirely.