Ball-based puzzlers often incite the yonder kid in me. The kid who lavishly wasted his time playing 3D Pinball on Windows XP or getting frustrated at wooden Labyrinth games because the ball didn’t go where I wanted it to. Such concepts are simple and while there aren’t many other facets to simply guiding a ball to a particular end-point, the reason why they’re so compulsively long-lasting in their appeal is because of the heightened sense of risk. That perilous decision to go one way and play it safe…or let greed (as much personal gratification) get in the way and aim for much more. Is this why Hyposphere exists then? To feed on mine — and I imagine plenty others’ - nagging compulsion to beat something. To get not just a high score but to also say you were the one (if not among the privileged few) to actually conquer said game’s vast assortment of levels which challenge not just one’s co-ordination, but also one’s patience.

Hyposphere is indeed a game that gives its players that smug “there ya’ go” mentality in presenting us what’s detailed as a hundred levels of navigating a small metallic ball-bearing to an end goal. And there’s nothing wrong with being smug; a lot of games bluntly address the challenge straight-away and there’s often an intriguing love-hate pull to this assortment of games. Obviously the premise of simply guiding a ball to an end goal doesn’t sound like much on paper and can be equated to being as lively or as engaging as say…drawing endless amounts of lines. But hey the latter concept has certainly proven itself this year, so why not a familiarly Super Monkey Ball-esque indie title structured around the typically indie developer “x amount of levels” structure? Answer: because, plain and simple, Hyposphere - even with the very assets it flaunts so proudly on the visual side - just isn’t that much fun or appealing to approach.

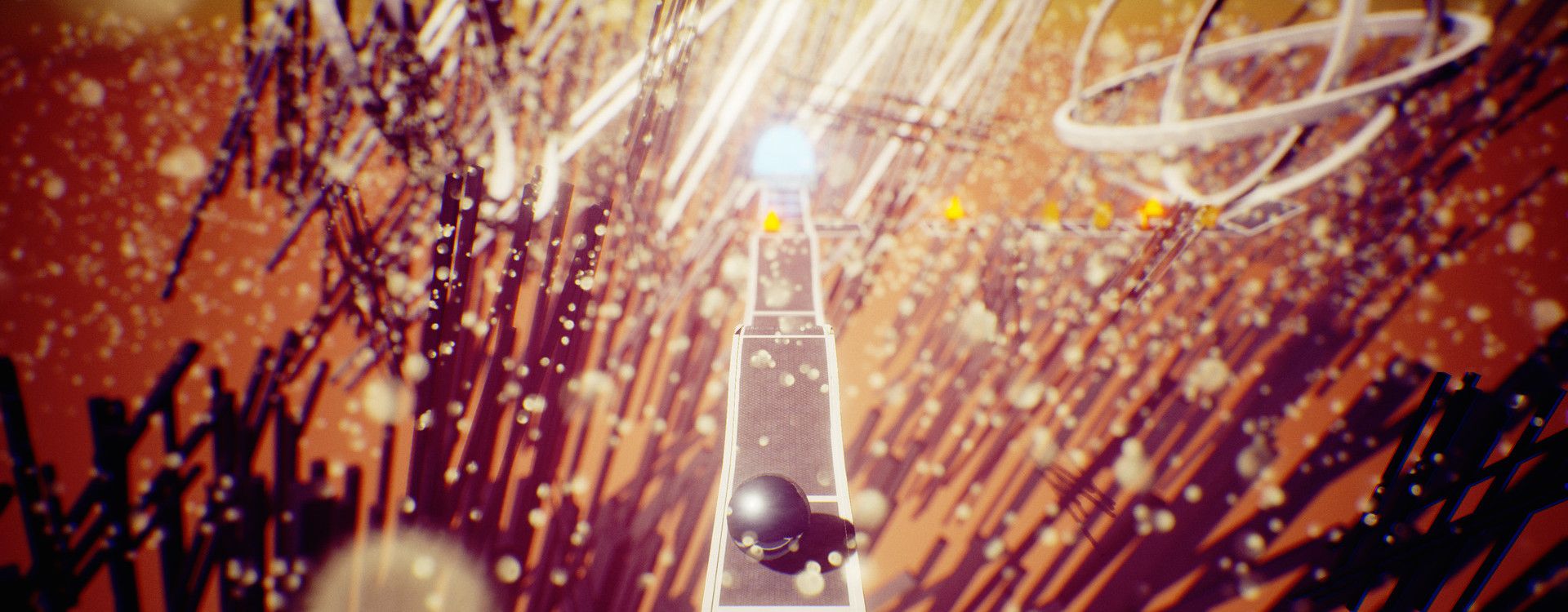

From the off, Atum Software paint themselves as a team who have unfortunately put far more than simply all their eggs in this one figuratively metaphorical basket. While it’s clearly evident the team know how to showcase what the [preferred] Unreal Engine can muster — with its glossy, richly-detailed graphics and notable addition of several “fan-favorite” post-processing effects — the truth is that the inspiring visuals only travel but a shallow way to masking the rather uninspiring presentation of everything else around it. When you find yourself looking at the very same stock imagery for button prompts and the soundtrack can be summed up as little more than a dozen strong (if well mixed) array of ten second loops on repeat, there comes a point, very early on, when Hyposphere already stretches its unique selling point rather thin.

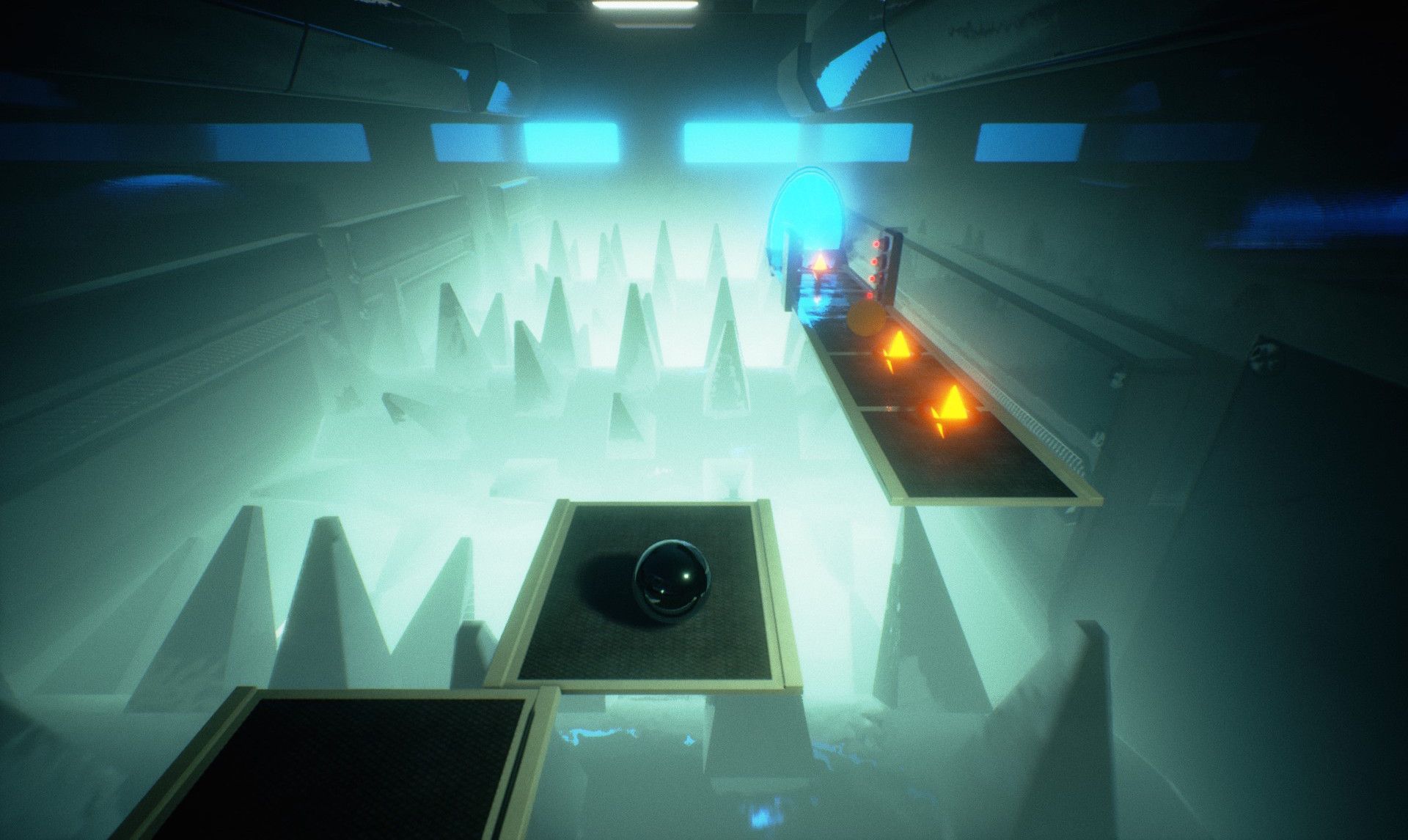

But there is a definite appeal and often nagging “one more go” pull to Hyposphere’s gameplay and when the controls maintain a level of consistency with the pre-defined rules on how your little ball bearing moves and, when applicable, how elements such as speed factor in, the short-term, pocket-size levels definitely hold their own charm from a challenge stand-point. The problem is Hyposphere’s programming can occasionally throw-up some quite baffling decisions with its physics, it’s hard not to feel a little cheated — especially when you’ve done everything right, are approaching the final stretch and ultimately fall off at the final hurdle due to the game’s hiccuping inconsistency with physics.

It would certainly be a lot more infuriating had the game be as scarce on lives as it tries to make out, but simply restarting the level moments before “death” will circumvent such a a loss and ultimately disproves the very need for lives in this game. And it’s certainly not the only game-breaking element that manages to rustle up on-screen; having readjusted the game’s sordid overuse of effects such as film grain, bloom, lens flare and chromatic aberration, I found the game would occasionally freeze — incurring a restart, but also an unnecessary restart at earlier levels. Hyposphere’s checkpoint system, further to that, is too both confusing and head-scratchingly poor in its placement.

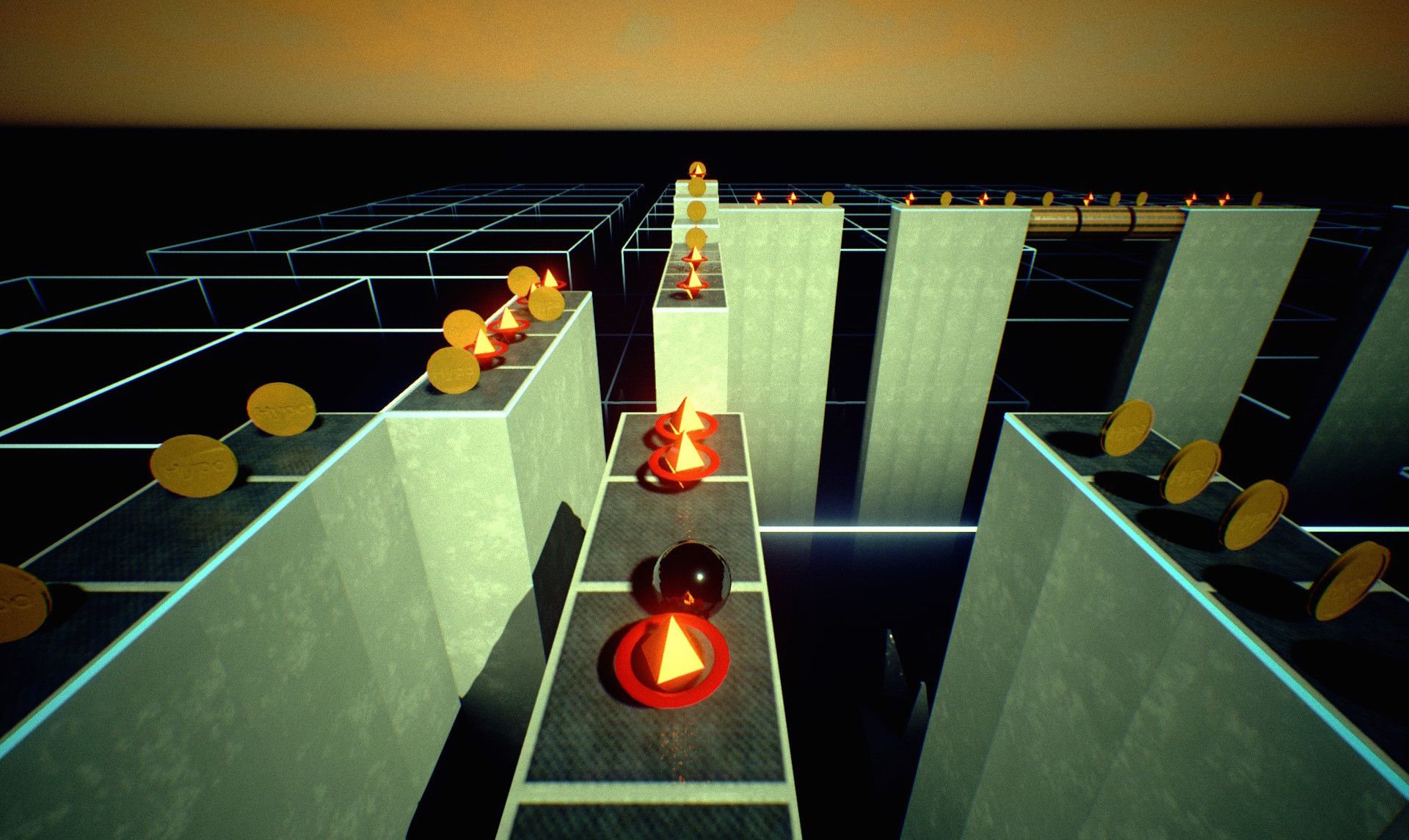

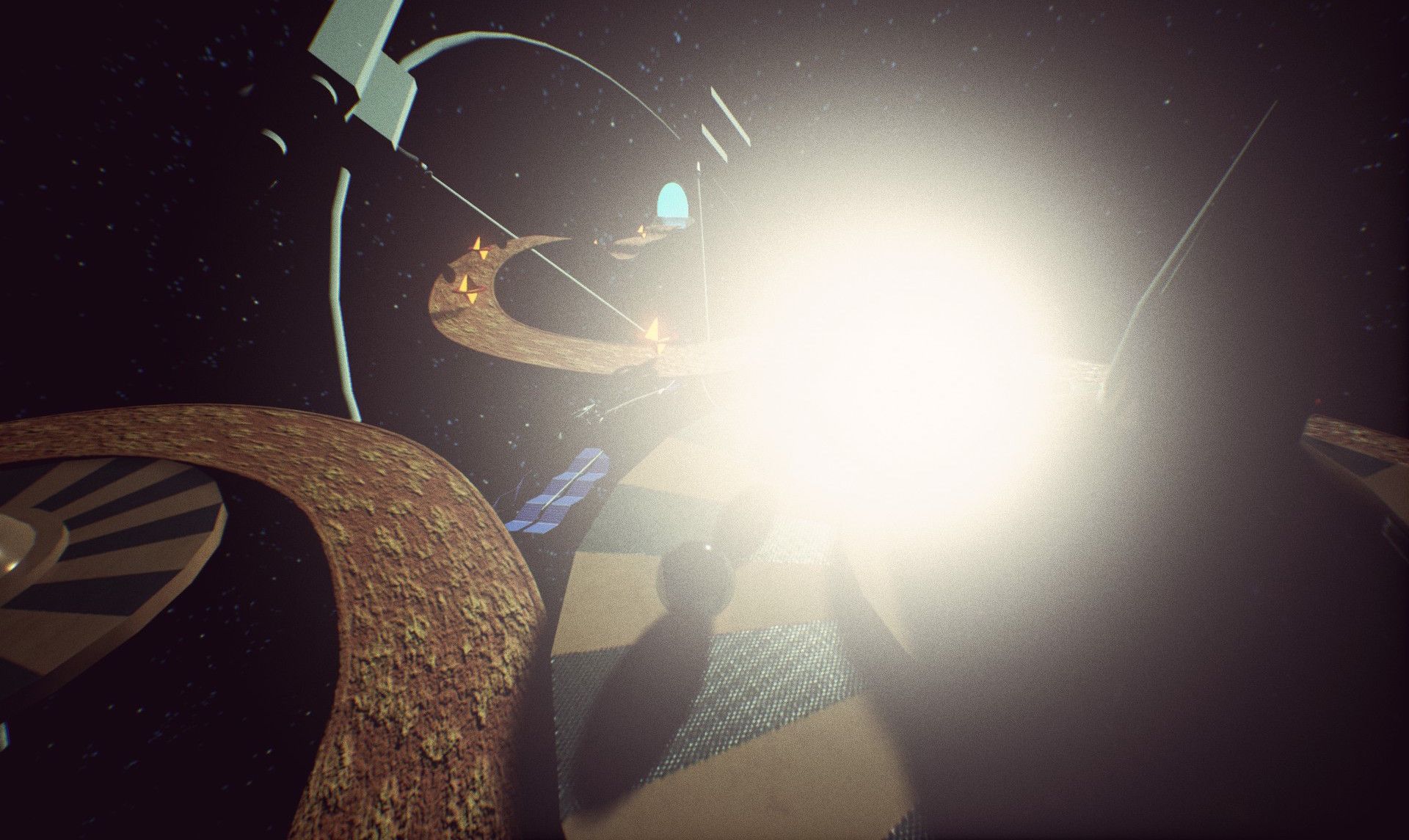

The fact the game’s level progression tends to jump all over the place both structurally and conceptually - shifting from visual cue to visual cue; to space to everything being digital and back to space again — adds little feeling of progression and the game’s requiring you to make it to an unspecified point in order to constitute a would-be “checkpoint” feels poorly communicated. But if we’re talking short-term -- and by short-term I mean incredibly small ounces of time revolving around each of the game’s thirty second-or-so duration levels — you can’t fault Atum’s understanding on how to coax players into approaching matters in more than one way.

While I wouldn’t necessarily go as far as to say the developer’s claim that their levels are “non-linear” and “can be played in different ways”, more often than not these obstacle course-like arrangements will usually split into two possible three different paths. Each with their own neatly-arranged allotment of platforms that move, twist, rotate and spin to add further pleasant complexity in, at the best times, very tense and nimbly delicate segments of gameplay. To that end, the somewhat elegant design certainly harkens back to a retro formulaic approach to platforming and seeing this executed with ball bearings, rather than a player-character, is intriguing if not wholly excelling in this respect.

Closing Comments:

Yet in the end, for all its slick, admittedly-impressive detail with its visual assets, Hyposphere tries too hard to impress from the surface without considering anymore for what lies underneath its many high-resolution environments that play out more like demonstrations than fully realized, fully finished video game levels. With its stock-reliant appearance and seemingly uncombed delivery, Hyposphere feels like a game hurriedly rushed out for presentation sake, with little else put into refining the experience underpinning it.