Playing Tartarus is possibly the closest I’ll ever come to experiencing what it’s like to try and fix something I don’t fully understand. The challenge and frustration didn’t come from trying to figure out what the solution to the problem was. My fellow crewmember almost always told me what I needed to accomplish. No, the trick was always in figuring out how to arrive at that solution. When Tartarus is working well, piecing through each challenge is a slow but rewarding experience that is all too rare in gaming these days. When Tartarus isn’t working, though, it’s the opposite: too much frustration for too little reward. At its core, Tartarus is a fun experience most puzzle game fans would enjoy. That core might have been buried a bit too deeply under small annoyances and at least one big problem, though.

Tartarus puts its players in the shoes of a man known only as “Cooper.” He’s a miner and the ship’s cook aboard the titular deep-space mining ship and is perhaps the least qualified among the crew to repair it in a crisis. Of course something catastrophic happens to the Tartarus and Cooper finds himself in the unenviable position of being the only one able to move around the ship to make repairs. There is one other crewmember around to help him out, but Mr. Andrews just so happens to be trapped like the rest and can only aid by giving instructions through the ship’s intercom. So ship’s cook or not, it’s up to Cooper to get the job done before the Tartarus either explodes or gets pulled down into Neptune. No pressure, right?

It might seem like an odd decision to put players into the shoes of a character who is wholly unprepared to get the job done, but doing this might actually turn out to be one of the game’s greatest strengths. Cooper and the player are on equal footing in this situation. He knows just as much as the player does and is not at all happy about it. He’ll talk to himself in frustration, have exasperated outbursts when he encounters a new twist to a challenge and take every opportunity to brag and pat himself on the back whenever he manages to complete a task. He's more of a partner on your journey through the game than he is an avatar, something that helps the game out quite a bit. He adds much needed levity and investment to an environment that would otherwise have a hard time holding one’s interest.

For the most part, the Tartarus is an eerily quiet place. Most of the time there’s actually nothing to hear at all beyond Cooper’s footsteps as he grudgingly trudges from one part of the ship to the next, not even ambient sounds or music. Aside from his brief exchanges with Andrews on the ship’s intercom, there’s nothing to hear except Cooper talking to himself. While this reinforces the feeling of isolation the game is going for, it also takes you out of the experience. Ships aren’t perfectly silent, so the lack of ambient noise in some areas was distracting. That said, the ship is visually believable. The Tartarus is every bit the dirty, industrial hulk that one would expect. It’s more floating oil rig than spaceship. Most of the spaces are cramped and dirty. Most rooms are poorly lit. The floors are covered in safety warnings and that bulkheads are lined with all manner of pipes and conduits. This is a vessel meant for difficult, dangerous work and the ship makes sure to remind players of that around every corner. It may look basic, but this is an environment that looks like it’s been lived in.

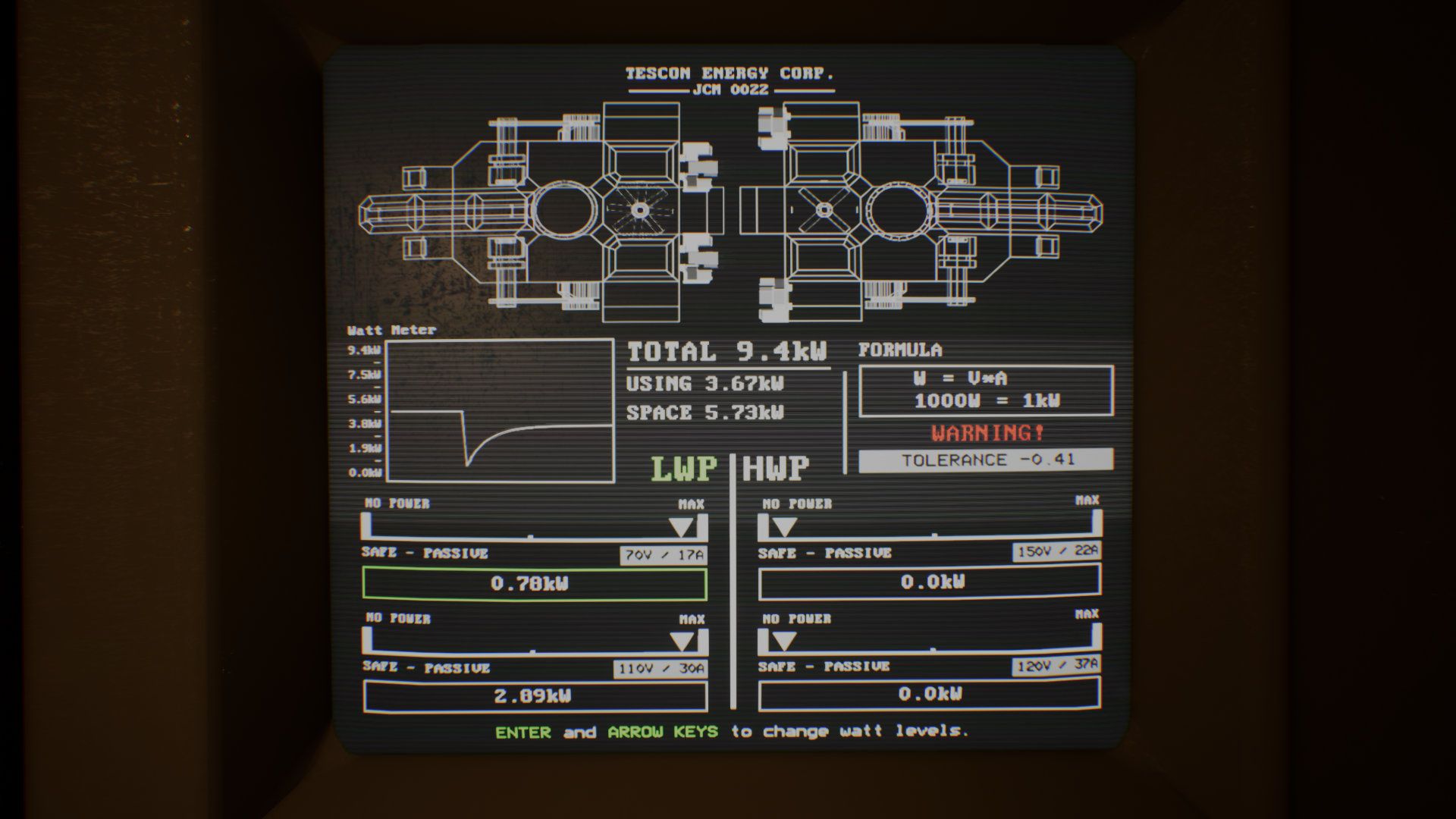

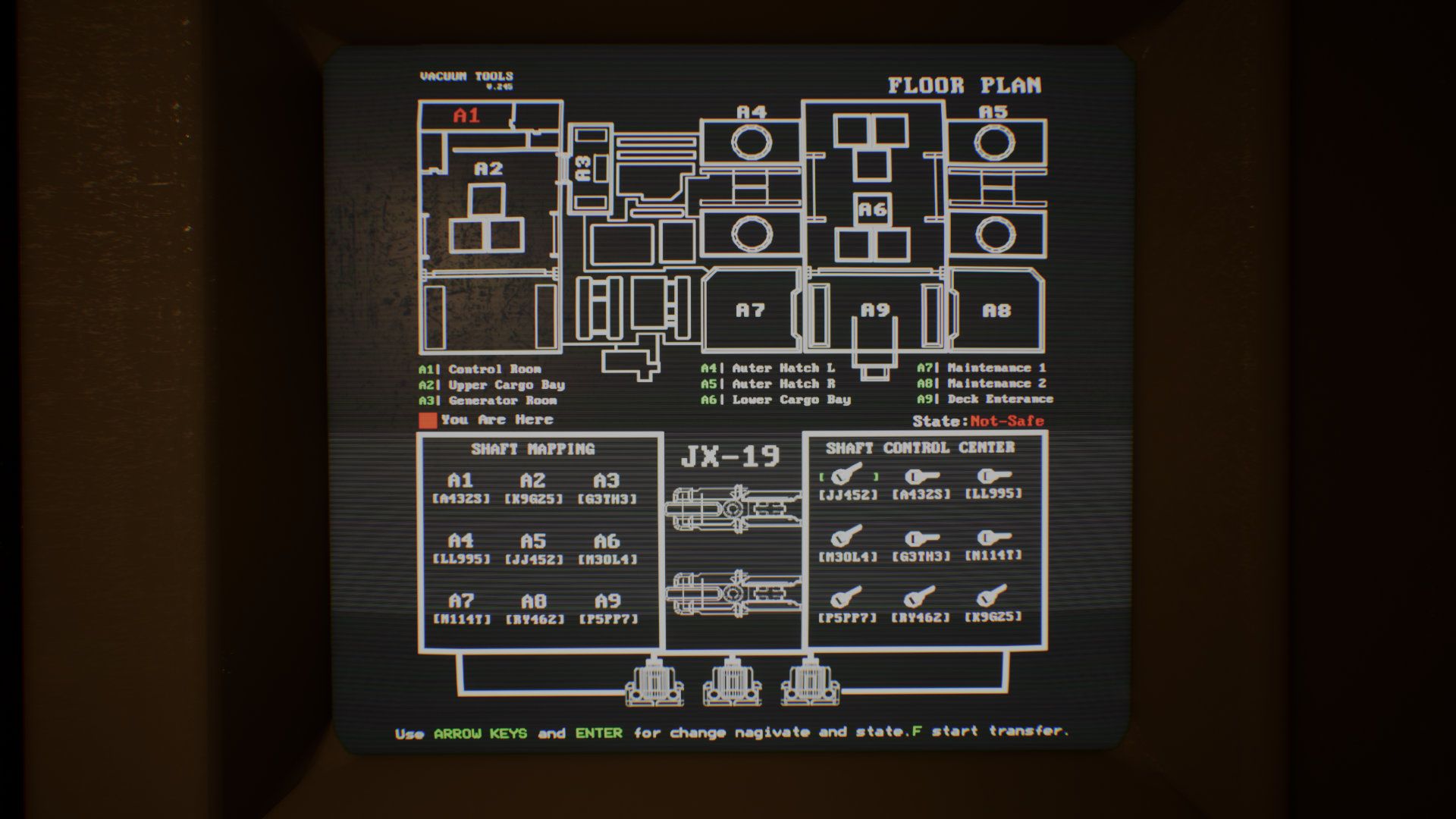

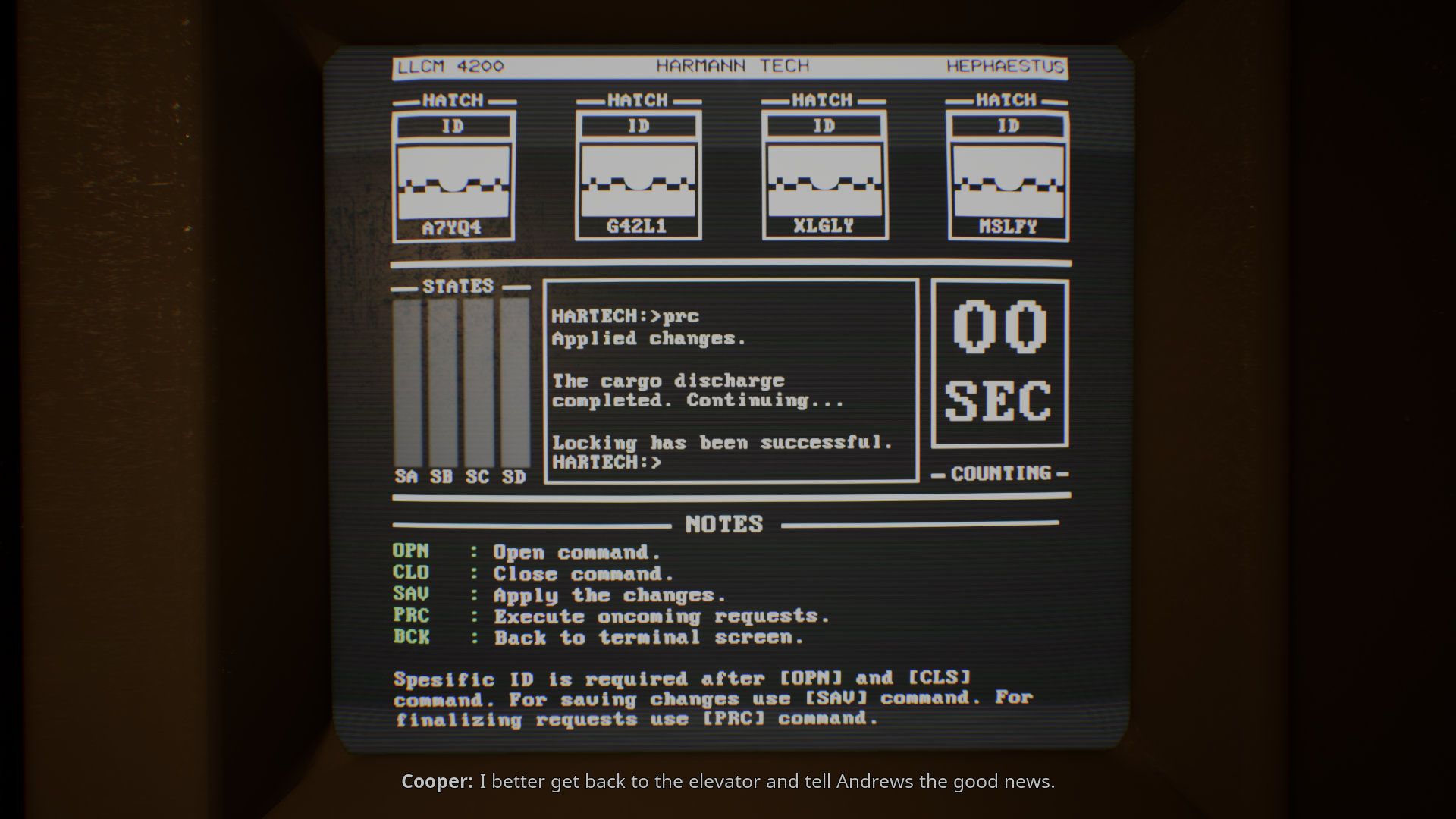

Cooper isn't there to wander around the ship pondering at the lack of ambient noise though is he? No, he’s there to fix it and that means learning how to use the ships “Farpoint OS.” This is where the real meat of Tartarus’ gameplay is found. For each problem on the ship, Cooper and the player have to figure out how to tell the system what they want it to do. It’s not a matter of clicking through folders to find the right data or program, though. A command-line based system, Farpoint is from the oldest of operating system schools. Players who’ve messed around with the Windows command prompt in the past may find it somewhat familiar, but this will be a new experience for everyone else. Put simply, Farpoint requires its users to outright tell it what they want by typing in the correct commands. If you don’t know the commands, then you’re not going to get far. Andrews tells Cooper how to get started, but from there he and the player are on their own. Beyond a list of commands and vague descriptions of their function that can be displayed via a global “help” command, the game offers no further hints or clues. Figuring out how to do what you want to do is the challenge here, one that feels rewarding once it’s overcome. The game’s purposeful vagueness, however, can work against it at times.

The puzzles are mostly straightforward enough that they can be solved with a bit of thought and note-taking. It’s only when the games asks the player to make logical leaps that issues arise. Tartarus' first challenge to Cooper is to escape the ship’s bridge by resetting its door’s hydraulic pistons. The basic task is to retrieve the default settings for the door and then enter them into the portion of the system actively controlling it. Since Cooper had to log into the terminal as Andrews, who happens to be the ship’s engineer, it stands to reason that the data he’s looking for would be in Andrews’ files. Sure enough, it’s there. Step one complete! Now the question is how to use that data. Digging through the other directories doesn’t reveal anything obvious and the help list descriptions don’t offer much insight. There are several files available that can be accessed with the “Scan” command, but again there’s nothing obvious. It turns out that the sticking point was the description for the “connect” command. The help list says it’s used to connect to a specific sector, but there’s no indication of how the system defines a sector. In this case, it was a matter of understanding what was being displayed when using the “scan” command. I had interpreted it as a status readout, but failed to recognize that the status’ being reported were those of each sector on the bridge. I made a guess and connected to the one labeled door and, sure enough, I was finally on the screen where I could input the door data I’d found earlier.

Most of the other puzzles require logical leaps or even shots in the dark to complete, but they’re doable if one is able to resist making too many assumptions and thoroughly considering all the information available. They’re frustrating, but much closer to the enjoyable headscratcher end of the spectrum then the unsolvable enigma end. On that note, it's repeatedly suggests that players use pen and paper to help themselves remember key pieces of info or work out problems. It’s advice that’s absolutely worth following. I’d used up a whole sheet by the time I was done!

Unfortunately, the game kind of falls flat whenever anything has to be done outside of the computer terminals. Taking in the ship as Cooper made his way from place to place was fun, but trying to find key items or panels was a pain. There’s nothing done visually to direct one’s attention to them and I often found myself wandering around for a while before finally seeing what I was looking for, discovering that there’s no reason to spend time exploring the Tartarus. There’s nothing to find; nothing to tell you about the crew, the ship or the world these people live in. Apart from the three or four key items needed for the puzzles, there’s nothing to find and not all that much more to see. Tartarus also struggles with physical tasks, asking the player to perform odd mouse movements to turn valves and wheels instead of just requiring a click or keystroke. Beyond these admittedly minor annoyances, the game does have one major issue.

*slight spoilers ahead. Skip this segment if you want to go in completely blind*

Towards the end of the game, there’s a sequence where in Cooper must activate a device while also staying completely hidden from the enemy stalking him. If Cooper is seen at all, even for an instant, he is shot and the whole sequence starts over. What’s more, the game takes its love for vague instructions a step further and gives no indication to the player as to where they need to go, what information they need to get or how they need to use it. All it provides is a general mission objective and sets you loose. This could have been fine if there had been time to think and no imminent danger, but that’s not the situation here. This is a forced, insta-fail, stealth section in a game about exploring a ship and solving puzzles on computer terminals. I’m thinking the developers wanted to give players a tense situation to overcome in the end, but it just doesn’t work and leaves the player with a bad taste in their mouth.

Closing Comments:

Tartarus doesn’t quite deliver the experience it’s aiming for. It’s light on story, but manages to make Cooper interesting and easy to identify with. The Tartarus is a crude hulk of a ship that succeeds in capturing that industrial, retro-futuristic, Aliens feel. It looks lived-in but is too quiet and empty to feel real. The lack of information and collectibles to find also feels like a missed opportunity. Learning how to use the Farpoint OS is mostly satisfying, but guesswork comes into play too often. All told, it took me about five hours to play through and for the price they’re asking, it’s enough. I’m the sort that enjoys digging around in computer systems, so while I was disappointed that there were only four major puzzles to work through, I was happy to playthrough what was there. Frustrating stealth segment aside, this can be recommended to those who enjoy feeling computer savvy or are just looking for a different kind of puzzle experience.